The Great Storm of 1703 was one of the most severe storms or natural disaster ever recorded in the southern part of Great Britain. The storm came in from the southwest on November 26, 1703.

Observers at the time recorded barometric readings as low as 973 millibars (measured by William Derham in south Essex),[1] but it has been suggested that the storm may have deepened to 950 millibars over the Midlands.

Damage

In London, approximately 2,000 massive chimney stacks were blown down. The lead roofing was blown off Westminster Abbey and Queen Anne had to shelter in a cellar at St. James's Palace to avoid collapsing chimneys and part of the roof. On the Thames, around 700 ships were heaped together in the Pool of London, the section downstream from London Bridge. HMS Vanguard was wrecked at Chatham. Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell's HMS Association was blown from Harwich to Gothenburg in Sweden before way could be made back to England.[2] Pinnacles were blown from the top of King’s College Chapel, in Cambridge.[3]

There was extensive and prolonged flooding in the West Country, particularly around Bristol. Hundreds of people drowned in flooding on the Somerset Levels, along with thousands of sheep and cattle, and one ship was found 15 miles inland.[4] At Wells, Bishop Richard Kidder was killed when two chimneystacks in the palace fell on the bishop and his wife, asleep in bed.[3] This same storm blew in part of the great west window in Wells Cathedral. Major damage occurred to the south-west tower of Llandaff Cathedral at Cardiff.

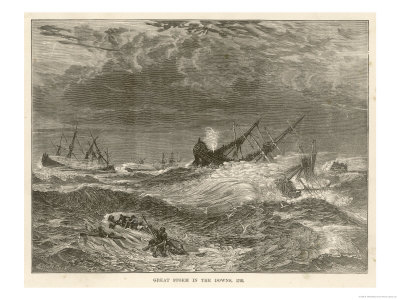

At sea, many ships (many returning from helping the King of Spain fight the French in the War of the Spanish Succession) were wrecked, including on the Goodwin Sands, HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Northumberland, HMS Mary, and HMS Restoration, with about 1,500 seamen killed particularly on the Goodwins. Between 8,000 and 15,000 lives were lost overall.

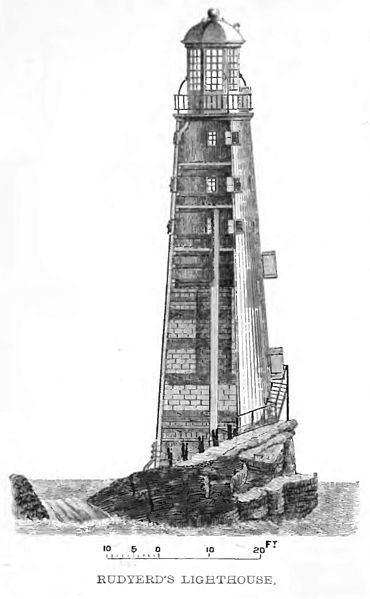

The first Eddystone Lighthouse off Plymouth was destroyed[3] on 27 November 1703 (Old Style), killing six occupants, including its builder Henry Winstanley (John Rudyard was later contracted to build the second lighthouse on the site).

A ship torn from its moorings in the Helford River in Cornwall was blown for 200 miles before grounding eight hours later on the Isle of Wight.[3] The number of oak trees lost in the New Forest alone was 4,000.

The storm of 1703 caught a convoy of 130 merchant ships and their Man of War escorts, the "Dolphin", the "Cumberland", the "Coventry", the "Looe", the "Hastings" and the "Hector" sheltering at Milford Haven. By 3pm the next afternoon losses included 30 vessels.[5]

Reaction

The storm, unprecedented in ferocity and duration, was generally reckoned by witnesses to represent the anger of God—in recognition of the "crying sins of this nation." The government declared 19 January 1704 a day of fasting, saying it "loudly calls for the deepest and most solemn humiliation of our people." It remained a frequent topic of moralizing in sermons well into the nineteenth century.[6]

Literary

The Great Storm also coincided with the increase in English journalism, and was the first weather event to be a news story on a national scale. Special issue broadsheets were produced detailing damage to property and stories of people who had been killed.

Daniel Defoe produced his full-length book, The Storm, published in July 1704, in response to the calamity, calling it "the tempest that destroyed woods and forests all over England." He wrote: "No pen could describe it, nor tongue express it, nor thought conceive it unless by one in the extremity of it." Coastal towns such as Portsmouth "looked as if the enemy had sackt them and were most miserably torn to pieces." Winds of up to 80mph destroyed more than 400 windmills.[7] Defoe reported in some the sails turned so fast that the friction caused the wooden wheels to overheat and catch fire.[8] He thought the destruction of the sovereign fleet was a punishment for their poor performance against the Catholic armies of France and Spain during the first year of the War of the Spanish Succession.[9]

In the English Channel, fierce winds and high seas swamped some vessels outright and drove others onto the Goodwin Sands, an extensive sand bank situated along the southeast coast of England and the traditional anchorage for ships waiting either for passage up the Thames estuary to London or for favorable winds to take them out into the Channel and the Atlantic Ocean.[10] The Royal Navy was badly affected, losing thirteen ships, including the entire Channel Squadron, [10] and upwards of fifteen hundred seamen drowned.[11]

- The third rate Restoration was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands; of the ship's company of 387 not one was saved.

- The third rate Northumberland was lost on the Goodwin Sands; all 220 men, including 24 marines were killed.

- The third rate (battleship)[10] Stirling Castle was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands. Seventy men, including four marine officers, were saved, but 206 men were drowned.

- The fourth rate Mary was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands. The captain and the purser were ashore, but Rear Admiral Beaumont and 268 other men were drowned. Only one man, whose name was Thomas Atkins, was saved. His escape was very remarkable - having first seen the rear admiral get onto a piece of her quarter-deck when the ship was breaking up, and then get washed off again, Atkins was tossed by a wave into the Stirling Castle, which sank soon after. From the Stirling Castle he was swept into a boat by a wave, and was rescued.[12]

- The fifth rate Mortar-bomb was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands and her entire company of 65 were lost.

- The sixth rate advice boat Eagle was lost on the coast of Sussex, but her ship's company of 45 were all saved.

- The third rate Resolution was lost at Pevensey on the coast of Sussex; all her ship's company of 221 were saved.

- The fifth rate Litchfield Prize was wrecked on the coast of Sussex; all 108 on board were saved.

- The fourth rate Newcastle was lost at Spithead. The carpenter and 39 men were saved, and the other 193 were drowned.

- The fifth rate fire-ship Vesuvius was lost at Spithead; all 48 of her ship's company were saved.

- The fourth rate Reserve was lost by foundering off Yarmouth. The captain, the surgeon, the clerk, and 44 men were saved; the other 175 members of the crew were drowned.[13]

- The second rate Vanguard was sunk in Chatham harbour. She was not manned and had no armament fitted; the following year she was raised for rebuilding.[14]

- The fourth rate York was lost at Harwich; all but four of her men were saved.

Lamb (1991) claimed 10,000 seamen were lost in one night, a far higher figure, about 1/3 of all the seamen in the British Navy.[15] Shrewsbury narrowly escaped a similar fate. Over 40 merchant ships were lost.[16]

No comments:

Post a Comment